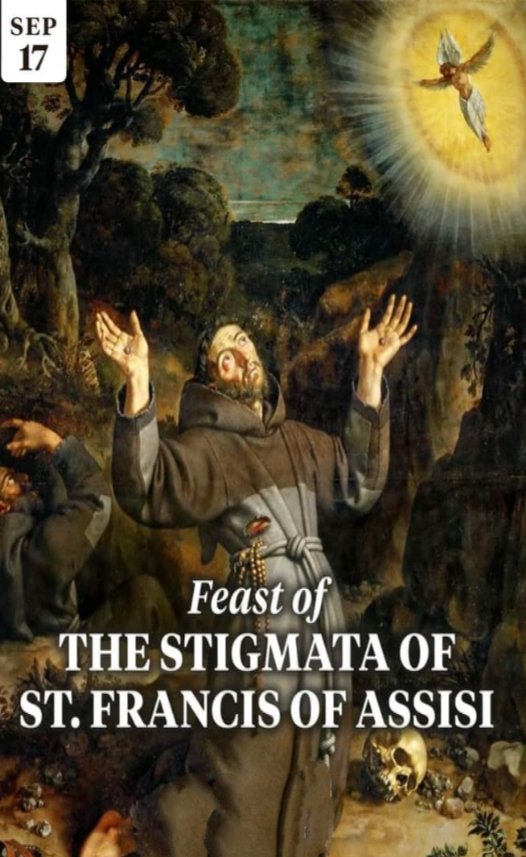

FEAST OF THE HOLY STIGMATA OF OUR HOLY SERAPHIC FATHER, SAINT FRANCIS OF ASSISI – 17 SEPTEMBER

Two years before his death, while at prayer on Mount Alvernia, the Seraphic Patriarch St. Francis of Assisi, was rapt in contemplation, and received in his own body the impression of the Sacred Wounds of Christ. Pope Benedict XI ordered the Feast of the Stigmata of St. Francis to be observed on September 17. Pope Paul V extended it to the whole Catholic world.

We celebrate on 17th September the stigmata of St. Francis of Assisi. Few saints have had a decisive influence on the civil and ecclesiastical history of all time as the Poverello of Assisi. And few have taken the evangelical maxims as far as this man who identified himself so much with Jesus Christ crucified, that he deserved to receive in his body the sacred stigmata.

THE STORY OF THE STIGMATA

After two days on the road, Francis and his companions reached the foot of La Verna on the vigil of the Assumption and prepared for the arduous climb. Francis was very weak, and his companions went to a peasant who lived in the area and asked him to lend them his donkey.

“Are you,” he asked them, “friars of that Brother Francis of Assisi about whom people say so much good?”

The brothers replied that they were, and that it was really for Brother Francis that they wanted the donkey. The peasant, with great devotion and care, got the donkey ready, led it to Francis, and helped him mount it. Then all set out on the road, the brothers in front, and behind them Francis on the donkey, led by its owner.

As they were going over a good stretch of the road, the man again asked his question. “Tell me,” he said, “are you Brother Francis of Assisi?” And when Francis assured him that he was, the peasant said, “Well, then, try to be as good as everyone thinks you are, because many people have great faith in you. So I urge you, never let there be anything in you different from what they expect of you.”

As soon as Francis heard these words, he got down from the donkey, knelt before the peasant and devoutly kissed his feet. He thanked him most humbly because he had taken the trouble to admonish him so charitably.

They reached the mid-point of their ascent. The sun beat straight down and scorching heat rose from the red-hot rock. Not a tree, a hedge, a blade of grass was there, only stones, desolate in the burning heat of midday. The owner of the donkey walked as if he had been blinded by the light. A dreadful thirst scalded his throat. Everything round about, parched, dried up, seemed to increase his preoccupation with his thirst. The mountain itself seemed to be pleading for water as it stretched toward an implacable sky.

The peasant began to complain. He said that he could not stand it any more, “I am dying of thirst. If I don’t have something to drink, I’ll suffocate in a minute!”

Francis had pity on him. He got off the donkey and knelt on the stone, under the flaming of sky. In the dazzling reflections that encircled him, he seemed to be praying not only for the man of La Verna but for every poor soul in thirst. Far away, the bells of the country churches rang out, announcing midday on the vigil of the feast of Assumption.

Finally Francis arose and told the peasant that God in His mercy had answered his prayer.

The man ran to the place Francis showed him and to his joy and astonishment saw a bubbling spring of clear water. It gushed from the harsh rock and ran gurgling down the slope. Eagerly he flung himself down on the ground and plunged his mouth, face, and hands into the fresh water and drank avidly.

When he had finished, it was the peasant who knelt at Francis’s feet, overjoyed by the miracle that had so helped and strengthened him, and that would certainly comfort others nearby who would hear about it from him. He would tell them that it was proof of Francis’ holiness.

But when he went back home on the same road, he wore himself out searching for that miraculous spring. In vain. The water had disappeared as it had come and the ground was once again as it had been earlier – bone-dry.

It was already late in the day when Francis and his companions reached the summit. Bells were no longer ringing, but on the plain were glowing fires lit in honor of the Virgin.

The next day Francis began his meditation. The cell by the beech tree did not seem sufficiently isolated from the others for him, so, with Brother Leo’s help, he selected another place, on the far side of a fearful chasm over which they put a piece of wood to serve as a bridge. No one was to come to him but Brother Leo, who would bring him a bit of bread and some water once during the day and again at night, at the hour of matins. Before crossing the chasm, Brother Leo was to call out, Domine, labia mea aperies (“Lord, open my lips”). He was to go forward only if Francis replied, Et os meum annuntiabit laudem tuam (“and my mouth shall proclaim Your praise”).

The succession of days began, distinguishable only by the rising and the setting of the sun, by the blazing and the dimming of the stars.

A great silence prevailed.

At evening, when the mountain reddened in the sunset, from his cell Francis heard the falcons cry as they wheeled in the cobalt sky. Then a shadow began to creep downward from La Penna; slowly it veiled the forest and filled the distant valley.

One of the falcons became his friend. It was a fierce and violent creature, the same color as the rock. Its black eyes shone ferociously in its little grey head, its claws contracted in its instinctual rapine, the hooked beak was ready for attack. But even its predatory savageness disappeared as it was gentled by Francis.

The falcon built a nest near his refuge, as the innocent turtle dove had once done. It hovered to listen to his words. In the heart of the night, at the hour of matins, it came to awaken him by repeating its cry and beating its wings nor would it leave until Francis had gotten up. At dawn it “would very gently sound the bell of its voice” to call Francis to prayer.

But this, says Thomas of Celano, was Francis’s victory, because his love was being repaid with love; “little wonder if all other creatures too venerated this eminent love of the Creator.”

At the hour of matins when Brother Leo came, earth and sky were linked in harmony and from the woods came the sharp odor of cyclamens. The woodlands were immobile in a light of dream, wrapped in the whiteness of the full moon. Dark tree trunks stood straight as the lances of an army of giants. The breeze would rise and a long murmur, like the sighing of the sea, pass over the tops of the trees.

On one of those nights Brother Leo came to the brink of the gorge and said the words agreed upon, “Lord, open my lips.”

No one replied. He crossed the log and looked in the cell. Francis was not there. He went further and walked through the woods. At last he saw Francis on his knees, his face and his hands raised to the sky. Over and over he said, “Who are you, my dearest God? And what am I, Your vilest little worm and useless little servant?” In the still night was a man overcome by his own insignificance as he confronted the immensity of God.

Later, Leo and Francis interrogated the Gospels, as Francis had done in the church of San Nicolò, after the night he spent with Bernardo di Quintavalle. And each of the three times they sought God’s will, the book opened of itself to the Passion of Christ.

On this night, it seems that the lamentations of the Holy Week in Greccio fill the silence and make it a night of anguish. Francis and Leo hear all the pain in the world rising like a tide against the side of the mountain.

And he who was the father of all wants to bear the cross of all. Francis has a vision of Jesus rising before him. He comes forward on pierced feet, uncovers His lacerated heart, stretches out His nail-marked hands, and repeats the words of the Last Supper: “This is My blood. Drink all of it.”

He has the tender face of those who suffer and endure more than their share of pain and abuse, who must drag crosses too heavy for them up exhausting hills. They collapse under the beatings life deals out to them, get up and go on, fall again. The mountain seems to be trembling under the blows of the hammers nailing them to their crosses. It echoes with the sounds of imprecations, everlasting derision, torture, and grief. Jesus becomes every suffering creature; life, an immense Calvary.

And Francis, kneeling before his cell, lifts up this fervent prayer:

“My Lord Jesus Christ, I pray You to grant me two graces before I die. The first is that during my life I may feel in my soul and in my body, as much as possible, that pain that You, dear Jesus, sustained in the hour of Your most bitter Passion. The second is that I may feel in my heart, as much as possible, that great love with which You, O Son of God, were inflamed in willingly enduring such suffering for us sinners.”

Francis’ prayer is answered. The life that began with a kiss to a leper, the life that has in it leper hospitals, prisons, battlefields in Arce and Perugia and Damietta, and all the places he found pain and suffering, has led now to this moment in the night before the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross.

He saw the mountain covered by light, the heavens open, and a burning seraph swiftly descend. Light blazed everywhere. Every blade of grass was clear and distinct in the dazzling light. Francis raised his eyes. The angel had his arms open, his feet stretched out. He was nailed to a cross. A living cross with six flaming wings, two raised over his knees, two covering his body, and two spread out in flight.

Then he was over Francis and rays darted from the wounds in his feet, his hands, his side, to pierce Francis’s hands, feet, and heart. Francis’s soul was caught up in a vortex of fire. An infinite joy filled him, and also infinite pain. He raised his arms toward the living Cross, only to fall unconscious against the stone.

The whole mountain of La Verna seemed to be burning, as if the sun were high. Shepherds, taking their flocks to the pasture-lands of the sea, were awakened. Muleteers got up, thinking it was dawn, and set out on the road again. They travelled on in what seemed bright daylight. And then they saw that immense light fade and vanish. Night returned, alive with stars.

According to his biographers, two years before his death, St. Francis of Assisi retired in Tuscany with five of his closest brothers, on the Mount La Verna, to celebrate the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin and prepare the feast of St. Michael the Archangel by forty days of fasting.

It was around the feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross. Kneeling before his cell, Francis was praying with outstretched arms awaiting dawn and was subject to an outstanding grace. The Lord crucified appeared to him in a figure of a six-winged seraph. After spending time with him in conversation, he departed leaving in the body of Francis the sacred stigmata printed.

Thus, this disciple and a passionate lover of Christ, who longed to resemble him, received this similar trait with Jesus Christ.

At the close of his life, when he was at the end of his strength, stigmatized, suffering without relief both physically and morally, that he reached the summit of perfect joy and composed the Canticle of the Creatures. He needed to attain the very heart of the Paschal Mystery of death and Resurrection before he could express this hymn in which the whole of creation is reconciled with God and in Him recovers its pristine integrity.

Our current preoccupations with freedom, with peace, with life, with happiness, with respect for God’s creation, all these aspirations are suggested to us by Francis of Assisi.

PRAYER

O Lord Jesus Christ, who, when the world was growing cold, in order to enkindle in our hearts the fire of your love, did renew the sacred marks of your Passion on the body of blessed Francis: mercifully grant, that with the aid of his merits and prayers we may ever bear our cross and bring forth worthy fruits of penance: Who lives and reigns with God the Father, in the unity of the Holy Spirit, God, forever and ever. Amen.

SOURCE: Arnaldo Fortini, (translated by Helen Moak), FRANCIS OF ASSISI, New York, N.Y.: The Crossroad Publishing Company, 1981, pages 554-558.http://www.fmm.org/pls/fmm/v3_s2ew_consultazione.mostra_pagina?id_pagina=1042