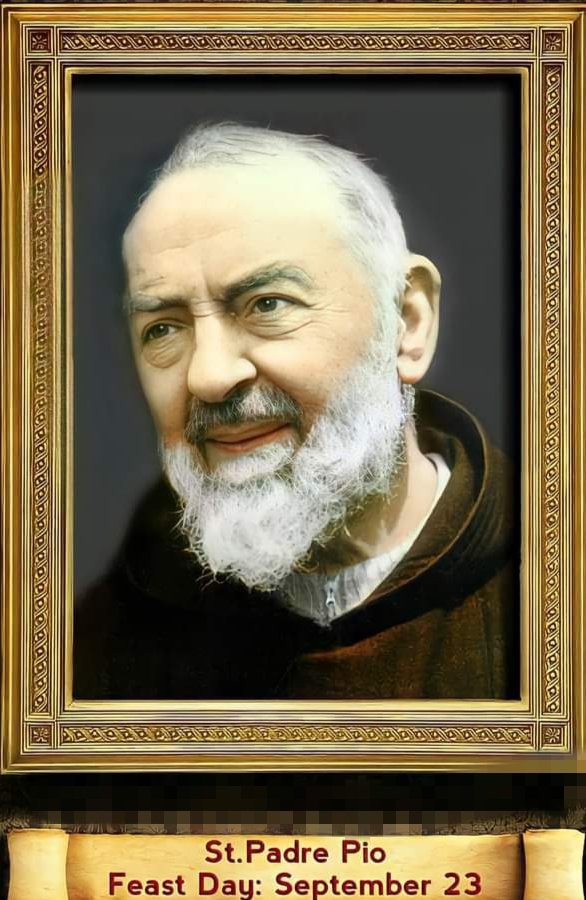

FEAST OF SAINT PADRE PIO

FEAST DAY – 23rd SEPTEMBER

Francesco Forgione was born to Grazio Mario Forgione (1860 – 1946) and Maria Giuseppa Di Nunzio (1859–1929) on May 25, 1887, in Pietrelcina, a town in the province of Benevento, in the Southern Italian region of Campania. His parents were peasant farmers. He was baptized in the nearby Santa Anna Chapel, which stands upon the walls of a castle. He later served as an altar boy in this same chapel.

He had an older brother, Michele, and three younger sisters, Felicita, Pellegrina, and Grazia (who was later to become a Bridgettine nun). His parents had two other children who died in infancy. When he was baptized, he was given the name Francesco. He stated that by the time he was five years old, he had already made the decision to dedicate his entire life to God. He worked on the land up to the age of 10, looking after the small flock of sheep the family owned.

Pietrelcina was a town where feast days of saints were celebrated throughout the year, and the Forgione family was deeply religious. They attended Mass daily, prayed the Rosary nightly, and abstained from meat three days a week in honor of Our Lady of Mount Carmel. Although Francesco’s parents and grandparents were illiterate, they narrated Bible stories to their children.

According to the diary of Father Agostino da San Marco (who was later his spiritual director in San Marco in Lamis) the young Francesco was afflicted with a number of illnesses. At six he suffered from severe gastroenteritis. At ten he caught typhoid fever. As a youth, Francesco reported that he had experienced heavenly visions and ecstasies. In 1897, after he had completed three years at the public school, Francesco was said to have been drawn to the life of a friar after listening to a young Capuchin who was in the countryside seeking donations.

When Francesco expressed his desire to his parents, they made a trip to Morcone, a community 13 miles (21 km) north of Pietrelcina, to find out if their son was eligible to enter the Order. The friars there informed them that they were interested in accepting Francesco into their community, but he needed to be better educated. Francesco’s father went to the United States in search of work to pay for private tutoring for his son, to meet the academic requirements to enter the Capuchin Order.

It was in this period that Francesco received the sacrament of Confirmation on 27 September 1899. He underwent private tutoring and passed the stipulated academic requirements. On 6 January 1903, at the age of 15, he entered the novitiate of the Capuchin friars at Morcone. On 22 January, he took the Franciscan habit and the name of Fra (Friar) Pio, in honor of Pope Pius I, whose relic is preserved in the Santa Anna Chapel in Pietrelcina. He took the simple vows of poverty, chastity and obedience.

Commencing his seven-year study for the priesthood, Fra Pio travelled to the friary of Saint Francis of Assisi in Umbria. At 17, he fell ill, complaining of loss of appetite, insomnia, exhaustion, fainting spells, and migraines. He vomited frequently and could digest only milk and cheese. Religious devotees point to this time as being that at which inexplicable phenomena allegedly began to occur. During prayers for example, Pio appeared to others to be in a stupor, as if he were absent. One of Pio’s fellow friars later claimed to have seen him in ecstasy, and allegedly levitating above the ground.

In June 1905, Pio’s health worsened to such an extent that his superiors decided to send him to a mountain convent, in the hope that the change of air would do him good. This had little impact, however, and doctors advised that he return home. Even there his health failed to improve. Despite this, he still made his solemn profession on 27 January 1907.

In 1910, Pio was ordained a priest by Archbishop Paolo Schinosi at the Cathedral of Benevento. Four days later, he offered his first Mass at the parish church of Our Lady of the Angels. His health being precarious, he was permitted to remain with his family until 1916 while still retaining the Capuchin habit. On 4 September 1916, however, Pio was ordered to return to his community life.

He moved to an agricultural community, Our Lady of Grace Capuchin Friary, located in the Gargano Mountains in San Giovanni Rotondo in the Province of Foggia. At that time the community numbered seven friars. He remained at San Giovanni Rotondo until his death in 1968, except for a period of military service. In the priesthood, Padre Pio was known to perform a number of successful conversions to Catholicism.

Pio was devoted to rosary meditations and said:

“The person who meditates and turns his mind to God, who is the mirror of his soul, seeks to know his faults, tries to correct them, moderates his impulses, and puts his conscience in order.”

He compared weekly confession to dusting a room weekly, and recommended the performance of meditation and self-examination twice daily: once in the morning, as preparation to face the day, and once again in the evening, as retrospection. His advice on the practical application of theology he often summed up in his now famous quote: “Pray, Hope, and Don’t Worry”. He directed Christians to recognize God in all things and to desire above all things to do the will of God.

Many people who heard of him traveled to San Giovanni Rotondo to meet him and confess to him, ask for help, or have their curiosity satisfied. Pio’s mother died at the village around the convent in 1928. Later, in 1938, Pio had his elderly father Grazio live with him. His brother Michele also moved in. Pio’s father lived in a little house outside the convent, until his death in 1946.

When World War I started, four friars from this community were selected for military service in the Italian army. At that time, Padre Pio was a teacher at the seminary and a spiritual director. When one more friar was called into service, Pio was put in charge of the community. On 15 November 1915, he was drafted and on December 6, assigned to the 10th Medical Corps in Naples. Due to poor health, he was continually discharged and recalled until on 16 March 1918, he was declared unfit for service and discharged completely.

People who had started rebuilding their lives after the war began to see in Padre Pio a symbol of hope. Those close to him attest that he began to manifest several spiritual gifts, including the gifts of healing, bilocation, levitation, prophecy, miracles, extraordinary abstinence from both sleep and nourishment (one account states that Padre Agostino recorded one instance in which Padre Pio was able to subsist for at least 20 days at Verafeno on only the Holy Eucharist without any other nourishment), the ability to read hearts, the gift of tongues, the gift of conversions, and pleasant-smelling wounds.

Padre Pio increasingly became well known among the wider populace. He became a spiritual director, and developed five rules for spiritual growth: weekly confession, daily Communion, spiritual reading, meditation, and examination of conscience. In August 1920, Pio led the blessing of a flag for a group of local veterans on the feast of the Assumption, and who were developing close links to local fascists. Pio subsequently met with Giuseppe Caradonna, a fascist politician from Foggia, and became his confessor and that of members of his militia.

Luzzatto suggests that Caradonna established a “praetorian guard” around Pio to protect him from removal by church authorities. An early biographer of Pio, Emanuele Brunatto, also mediated between Pio and the leaders of the growing Italian Fascist movement. Brunatto later donated his locomotive manufacturing company to Pio, which boosted the purchase of stocks by shareholders.” Brunatto’s publisher, Giorgio Berlutti, had been an enthusiastic supporter of Mussolini’s March on Rome, and used the biography to raise Pio’s profile.

It has been suggested that “a clerical-fascist mixture developed around Padre Pio”. According to a German article quoting Luzzatto, but without giving the exact source of Luzzatto’s words, “Pio also took a positive attitude towards Benito Mussolini”. By 1925, Pio had converted an old convent building into a medical clinic with a few beds intended primarily for people in extreme need. In 1940, a committee was set-up to establish a bigger clinic and donations started to be made. Construction began in 1947.

According to Luzzatto, the bulk of the money for financing the hospital came directly from Emanuele Brunatto, a keen follower of Pio, who had made his fortune in the black market in German-occupied France. The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) also contributed funding – 250 million Italian lire. Lodovico Montini, head of Democrazia Cristiana, and his brother Giovanni Battista Montini (later Pope Paul VI) facilitated engagement by UNRRA.

The hospital was initially to be named “Fiorello LaGuardia”, but eventually presented as the work of Pio himself. The Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza (English: Home for Relief of Suffering) opened in 1956. Pio handed direct control to the Holy See. However, in order that Pio might directly supervise the project, Pope Pius XII granted him a dispensation from his vow of poverty in 1957. Some of Pio’s detractors have subsequently suggested there had been misappropriation of funds.

The Vatican initially imposed severe sanctions on Pio in the 1920s to reduce publicity about him: it forbade him from saying Mass in public, blessing people, answering letters, showing his stigmata publicly, and communicating with Padre Benedetto, his spiritual director. The church authorities decided that Pio be relocated to another convent in northern Italy. The local people threatened to riot, and the Vatican left him where he was. A second plan for removal was also changed.

Nevertheless, from 1921 to 1922 he was prevented from publicly performing his priestly duties, such as hearing confessions and saying Mass. From 1924 to 1931, the Holy See made statements denying that the events in Pio’s life were due to any divine cause. Two months later, on July 26, pathologist Amico Bignami arrived in San Giovanni Rotondo. Bignami conducted a medical examination of Pio’s wounds in 1919 and launched several hypotheses, among which was that the wounds were a skin necrosis that was hindered from healing by chemicals such as iodine tincture.

Festa was a physician who examined Pio in 1919 and 1920. He was obviously impressed by the fragrance of the stigmata. Festa, as Bignami before, had described the side wound as cruciform. In his report to the Holy Office of 1925, Festa arrived at a benevolent verdict and attacked Gemelli’s critical view of Pio’s stigmata, with theological arguments playing the lead role.

The Bishop of Volterra, Raffaele Rossi, Carmelite, was formally commissioned on June 11, 1921 by the Holy Office to make a canonical inquiry concerning Father Pio.

Rossi began his Apostolic Visitation on June 14 in San Giovanni Rotondo with the interrogation of witnesses, two diocesan priests and seven friars. After eight days of investigation, he finally completed a benevolent report, which he sent to the Holy Office on October 4, 1921 — the feast of St. Francis of Assisi. The extensive and detailed report essentially stated the following: Father Pio, of whom Rossi had a favorable impression, was a good religious and the San Giovanni Rotondo convent was a good community.

The stigmata cannot be explained, but certainly are not a work of the devil or an act of gross deceit or fraud; neither are they the trick of a devious and malicious person. During the interviews with the witnesses, which Rossi undertook a total of three times, he let himself be shown the stigmata of the then 34-year-old Father Pio. Rossi saw these stigmata as a “real fact”.

In his notes, which have been put directly on paper, and the final report, Rossi describes the shape and appearance of the wounds. Those in the hands were “very visible”. Those in the feet “were disappearing. What could be observed resembled two dot-shaped elevations with whiter and gentler skin.” As for the chest, it says: “In his side, the sign is represented by a triangular spot, the color of red wine, and by other smaller ones, not anymore, then, by a sort of upside-down cross such as the one seen in 1919 by Dr. Bignami and Dr. Festa.”

Rossi also made a request to the Holy Office, a chronicle to consult with Father Pio, who is assembling Father Benedetto, or at least to have the material he has collected so that one day one can write about the life of Father Pio. When Rossi asked him about bilocation, Pio replied: “I don’t know how it is or the nature of this phenomenon—and I certainly don’t give it much thought—but it did happen to me to be in the presence of this or that person, to be in this or that place;

I do not know whether my mind was transported there, or what I saw was some sort of representation of the place or the person; I do not know whether I was there with my body or without it.”. Pio was said to have had the gift of reading souls and the ability to bilocate, among other preternatural phenomena. He was said to communicate with angels and work favors and healings before they were requested of him. The reports of preternatural phenomena surrounding Padre Pio attracted fame and amazement. The Vatican was initially skeptical.

In 1947, Father Karol Józef Wojtyła (later Pope John Paul II) visited Padre Pio, who heard his confession. Austrian Cardinal Alfons Stickler reported that Wojtyła confided to him that during this meeting, Padre Pio told him he would one day ascend to “the highest post in the church, though further confirmation is needed.” Stickler said that Wojtyła believed that the prophecy was fulfilled when he became a cardinal. John Paul’s secretary, Stanisław Dziwisz, denies the prediction, while George Weigel’s biography Witness to Hope, which contains an account of the same visit, does not mention it.

According to tradition, Bishop Wojtyła wrote to Padre Pio in 1962 to ask him to pray for Wanda Poltawska, a friend in Poland who was suffering from cancer. Later, Poltawska’s cancer was apparently found to be in spontaneous remission. Medical professionals were seemingly unable to offer an explanation for the phenomenon. By 1933, the tide began to turn.

Pope Pius XI ordered a reversal of the ban on Padre Pio’s public celebration of Mass, arguing, “I have not been badly disposed toward Padre Pio, but I have been badly informed.” In 1934, the friar was again allowed to hear confessions. He was also given honorary permission to preach despite never having taken the exam for the preaching license. Pope Pius XII, who assumed the papacy in 1939, even encouraged devotees to visit Padre Pio.

Finally, in the mid-1960s Pope Paul VI (pope from 1963 to 1978) dismissed all accusations against Padre Pio. Pio died in 1968 at the age of 81. His health deteriorated in the 1960s, but he continued his spiritual works. On 21 September 1968, the day after the 50th anniversary of his receiving the stigmata, Padre Pio felt great fatigue. The next day, on 22 September 1968, he was supposed to offer a Solemn Mass, but feeling weak, he asked his superior if he might say a Low Mass instead, as he had done daily for years.

Due to a large number of pilgrims present for the Mass, Padre Pio’s superior decided the Solemn Mass must proceed. Padre Pio carried out his duties but appeared extremely weak and frail. His voice was weak, and, after the Mass had concluded, he nearly collapsed while walking down the altar steps. He needed help from his Capuchin brothers. This was his last celebration of the Mass.

Early in the morning of 23 September 1968, Pio made his last confession and renewed his Franciscan vows. As was customary, he had his rosary in his hands, though he did not have the strength to pray the Hail Marys aloud. Till the end, he repeated the words “Gesù, Maria” (Jesus, Mary). At around 2:30 a.m., he said, “I see two mothers” (taken to mean his mother and Mary). At 2:30 a.m. he died in his cell in San Giovanni Rotondo. With his last breath he whispered, “Maria!”

His body was buried on 26 September in a crypt in the Church of Our Lady of Grace. His Requiem Mass was attended by over 100,000 people. He had often said, “After my death, I will do more. My real mission will begin after my death.” The accounts of those who stayed with Padre Pio till the end state that the stigmata had completely disappeared without a scar. Only a red mark “as if drawn by a red pencil” remained on his side, but it disappeared.

In 1982, the Holy See authorized the archbishop of Manfredonia to open an investigation to determine whether Pio should be canonized. The investigation continued for seven years. In 1990, Pio was declared a Servant of God, the first step in the process of canonization. The investigation, however, did not lead to any public factual clearance by the Church on his previous ‘excommunication’ or on the allegations that his stigmata were not of a supernatural kind. Moreover, Pio’s stigmata were remarkably left out of the obligatory investigations for the canonization process, in order to avoid obstacles prohibiting a successful closure.

Beginning in 1990, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints debated how Padre Pio had lived his life, and in 1997 Pope John Paul II declared him venerable. A discussion of the effects of his life on others followed. Cases were studied such as a reported cure of an Italian woman, Consiglia de Martino, associated with Padre Pio’s intercession. In 1999, on the advice of the Congregation, John Paul II declared Padre Pio blessed. A media offensive by the Capuchins was able to realise a broad acceptation of the contested saint in society.

After further consideration of Padre Pio’s virtues and ability to do good even after his death, including discussion of another healing attributed to his intercession, John Paul II declared Padre Pio a saint on 16 June 2002. An estimated 300,000 people attended the canonization ceremony in Rome. The remains of Saint Pio were brought to the Vatican for veneration during the 2015–2016 Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy. Saint Pio and Saint Leopold Mandic were designated as saint-confessors to inspire people to become reconciled to the Church and to God, by the confession of their sins.

PRAYER

Dear God, You generously blessed Your servant, St. Pio of Pietrelcina, with the gifts of the Spirit, marking his body with the five wounds of Christ Crucified, as a powerful witness to the saving Passion and Death of Your Son.

St. Pio labored endlessly in the confessional for the salvation of souls. With reverence and intense devotion in the celebration of Mass, he invited countless men and women to a greater union with Jesus Christ in the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist.

We pray to obtain our petitions through the intercession of St. Pio of Pietrelcina. Amen

(Prayer source: padrepio.com)