FEAST OF SAINT WENCESLAUS, DUKE OF BOHEMIA, MARTYR

FEAST DAY – 28th SEPTEMBER

Today’s saint, Wenceslaus, Duke of Bohemia, c. 907 – 929, was felled in a fateful encounter with his brother Boleslaus the Cruel. Wenceslaus was already famous when he died so young and so dramatically, leaving a lasting legacy for his memory to last.

He was recognized by the Church as a martyr, posthumously given the title of King, and quickly became an iconic figure to the Bohemian people such that his Feast Day, September 28th, is a national holiday in the modern Czech Republic.

Wenceslaus lived as Christianity was still dawning in central Europe. German missionaries had been laboring for a few generations with success, but underneath the visible layer of a Christian culture there was a substrata of paganism that was rock hard.

Central and Eastern Europe were passing through the normal stages of evangelization, as an age-old culture with all its customs and traditions was slowly pushed back by a greater force moving like a glacier. Catholicism had moved into Bohemia by the 900s, but the religious landscape was not yet monolithic.

As our martyr’s death attests, religious and political divisions ran cracks through the culture. The grandfather of Wenceslaus may have been converted by no less than Saints Cyril and Methodius themselves.

His grandmother Ludmila was an ardent Catholic and oversaw Wenceslaus’ excellent education in which he learned to read and write both Slavonic and Latin. Wenceslaus’ mother, Drahomira, clung to the old ways, though she was nominally a Christian.

When Drahomira thought Ludmila was encouraging Wenceslaus to assume power as a teen, Drahomira had her mother-in-law strangled to death with her own veil.

Once he did take power, Wenceslaus banished his own mother, solidified control of western Bohemia, and became an honorable ruler. He followed the law, favored education, and promoted the form of Christianity practiced in Germany, not in the east.

This was a fateful decision. Poland, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia are Slavic peoples of the Latin Rite, unlike their Orthodox and Byzantine Rite Slavic cousins just to the east.

Wenceslaus was pro-Western theologically and liturgically, while retaining his Slavic identity and independence in other essential matters. This pattern was to endure, giving Slavic Catholicism its unique features.

But for all of Wenceslaus’ brief successes, in the shadows lurked Boleslaus, creating a power center in eastern Bohemia. When Wenceslaus’ wife gave birth to a son, Boleslaus knew he would not succeed his brother, so he plotted his murder.

Boleslaus and his henchman struck down the young duke Wenceslaus in 929 on the Feast of Saints Cosmas and Damian and on the Vigil of Saint Michael the Archangel.

“Brother, may God forgive you” were our martyr’s last words. A young duke, killed by a jealous brother became a Czech icon. Saint Wenceslaus is Patron Saint of the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

(Source: mycatholiclife)

PRAYER

Saint Wenceslaus, you were the epitome of a just and compassionate leader in your brief reign. You saw it as your sacred duty to glorify the true God and and uphold His religion. Help all rulers and leaders to see morality, liturgy, prayer, and catechesis as the bedrock of a just society.

You forgave your brother the same way Christ forgave humanity. May you occupy a princely seat in the Kingdom of God. Amen

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

ALSO CELEBRATED

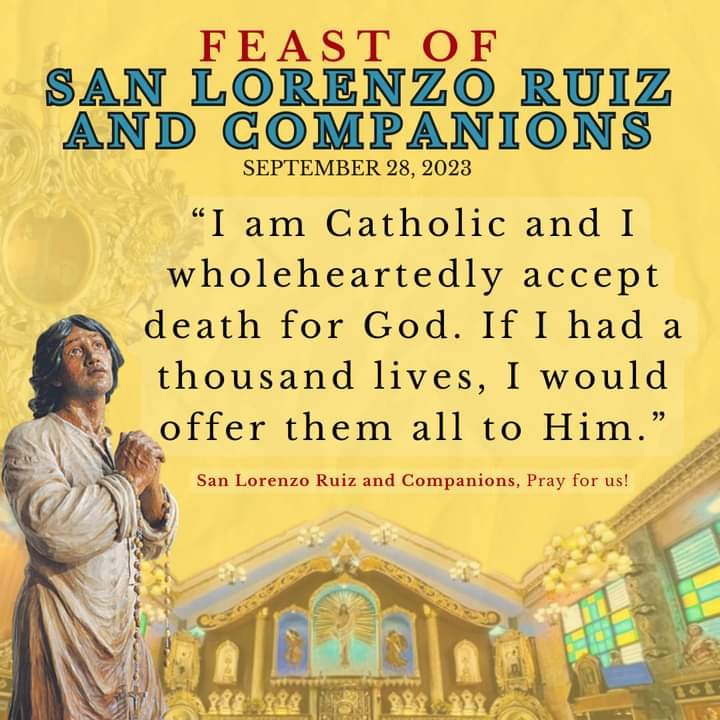

SAINTS LAWRENCE RUIZ AND COMPANIONS, MARTYRS

FEAST DAY – 28 SEPTEMBER

In 1549, Saint Francis Xavier and two Jesuit companions first reached Japanese soil with the Gospel. By the end of the century, Japan had an estimated 300,000 converts to the faith. By the 1580s, the Tokugawa shogun had become suspicious of Western Christianity, fearing that its spread could lead to European colonization. As a result, edicts were issued that outlawed Christianity. This led to thousands of martyrdoms between the years 1597 and 1639. Of those martyrs, twenty-six were canonized as saints in 1862, 205 were beatified in 1867, sixteen were canonized in 1987, two were beatified in 1989, and 188 were beatified in 2008. The saints commemorated on 28 September, Saints Lawrence Ruiz and Companions, are those sixteen who were canonized on 18 October, 1987, by Pope John Paul II.

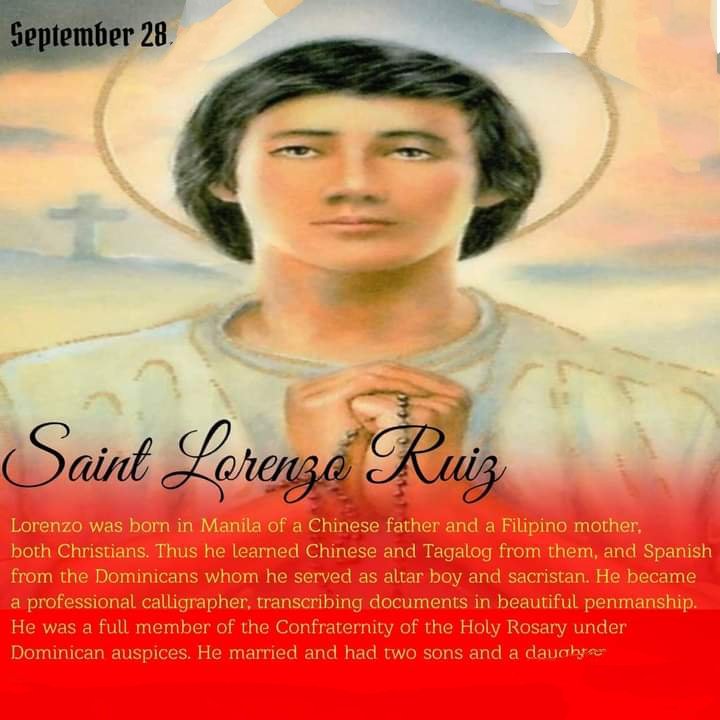

Lorenzo (Lawrence) Ruiz was born to a Chinese father and a Filipino mother in Binondo, Manila. The city of Binondo was established only six years before Lawrence’s birth by the Spanish governor for Chinese settlers who had converted to Catholicism. It soon became a vibrant and multicultural district, marked by many mixed marriages between Chinese and Filipinos, playing an important role in Manila’s commercial and cultural life. As a child, Lawrence learned Chinese from his father and Filipino from his mother, both of whom were Catholics.

He was an altar boy at the local Dominican-run church, where he also received an education. Excelling in penmanship, he became employed as a scrivener, writing official documents, recording transactions, and keeping other written records. As he grew, he continued to be involved in parish life, joined the Confraternity of the Most Holy Rosary, and lived a normal life. In his late teens or early twenties, Lawrence married a woman named Rosario, and they had three children: two sons and a daughter.

During Lawrence’s lifetime, c. 1600–1637, Spanish colonizers ruled the Philippines. Although they brought many benefits to the land, including numerous missionaries, the colonizers also often ruled with injustice. For instance, if a native Filipino killed a Spaniard, the crime would be met with swift retribution and severe punishment, disproportionately harsh towards the natives. Although an established legal system existed, it favored the Spaniards, so when a Filipino was accused of a crime, true and equal justice was not always guaranteed.

Unfortunately, Lawrence’s life took a tragic turn when, in 1636, around the age of thirty-six, he was falsely accused of a crime against a Spaniard, most likely murder, though records aren’t definitive. To escape unjust persecution, Lawrence hid from the authorities and boarded a ship with three Dominican priests, a Japanese priest, and a layman. Although the ship might have been initially destined for a peaceful Japanese port, it landed in Okinawa, Japan, where Catholic persecution was intense.

Shortly after the six arrived, the Tokugawa shogun became aware of their presence and had the group arrested. They were interrogated and informed they must leave Japan, to which they agreed. However, the shogun, unsatisfied with merely having them leave, also demanded they renounce their faith. This was a common tactic in Japan, aimed to eradicate the faith from the land. The belief was that if Christians publicly denounced their faith, other Japanese would see this as a sign of weakness and also abandon the faith. The group refused.

For over a year, this group of six remained imprisoned and were eventually transferred to Nagasaki. Throughout their captivity, they endured unimaginable cruelty. Water was poured down their throats, boards were placed on their abdomens, and they were subsequently jumped on, forcing the water out through their mouths, noses, and ears. They were cut and pricked with sharp bamboo, and endured severe psychological torture.

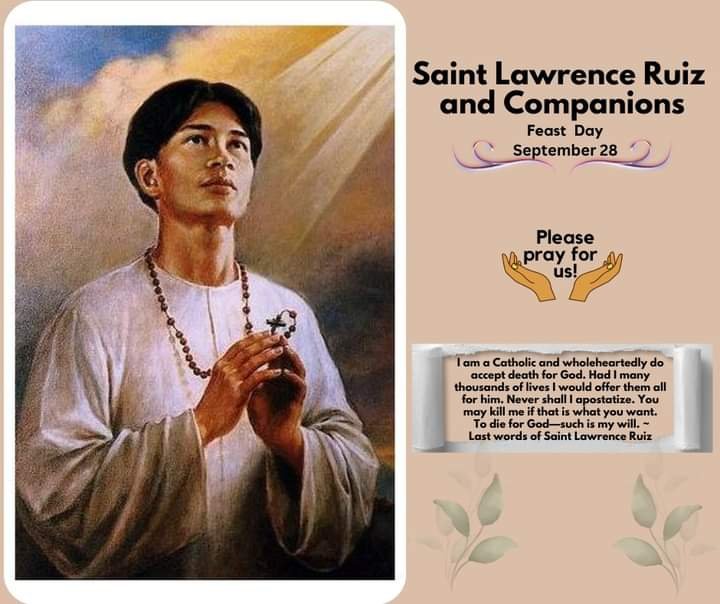

One priest died on September 24, 1637. After that, two others considered renouncing their faith but found their resolve and held firm. Lawrence asked the torturers, “I would like to know if, by apostatizing, they will spare my life?” No answer came, and Lawrence remained resolute in his faith. They were then tightly bound to restrict blood flow and hung over pits.

With one arm freed, they were told they merely needed to signal apostasy with that arm. They refused, remaining in that state for three days. Lawrence eventually proclaimed, “I am a Catholic and wholeheartedly accept death for God. Had I many thousands of lives, I would offer them all for Him. Never shall I apostatize. You may kill me if that is what you want. To die for God—such is my will.” Lawrence and his lay companion Lazaro died soon after, with the remaining three priests beheaded. They died on September 28 or 29, 1637.

The six martyrs included two laymen: Lawrence Ruiz and Lazaro of Kyoto; two Spanish Dominican priests, Fathers Antonio González and Miguel González de Aozaraza de Leibar; French priest Father Guillaume Courtet; and Japanese Dominican Father Vincentius Shiotsuka.

Also honored are five priests, two religious brothers, and three laypeople who were martyred in 1633 and 1644. The priests were Fathers Dominic Ibáñez de Erquicia Pérez de Lete, Jordan Ansalone, Luke of the Holy Spirit Alonso Gorda, Jacobo Kyushei Gorōbyōe Tomonaga de Santa María, and Thomas Rokuzayemon. The religious brothers were Francis Shōyemon and Matthew Kohioye. The laypeople were Marina of Omura, Magdalene of Nagasaki, and Michael Kurobioye.

As we honor these heroic witnesses to the Catholic faith, ponder the fact that their lives concluded with exceptional pain and suffering. Still, their eternal lives in Heaven are now celebrated with the highest praises. Saint Lawrence Ruiz, was the first Filipino martyr, making his witness greatly revered among Filipino Catholics who seek his intercession. He is Patron Saint of the Philippines, Filipinos, immigrants, the poor, separated families, and altar servers.

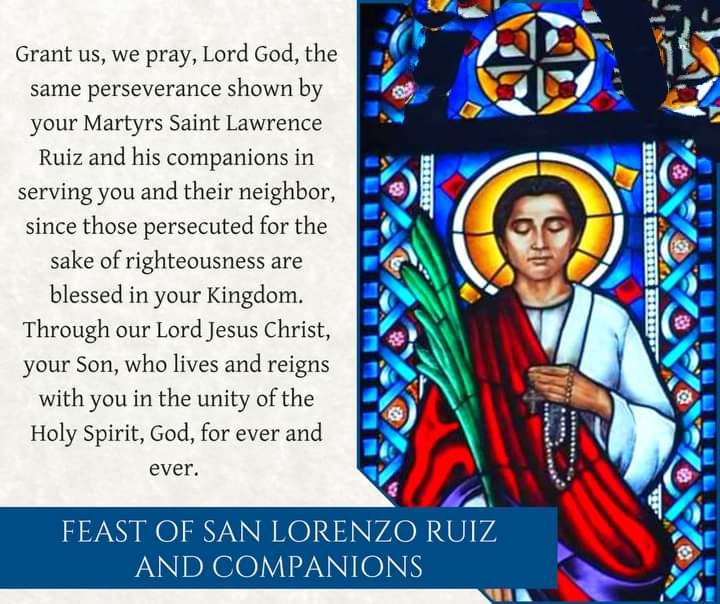

PRAYER

Saint Lawrence, along with the numerous other Japanese martyrs from the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, did more for the faith by courageously sacrificing their lives than they could have by living comfortably. Love is sacrificial, and while we might not be called to be martyrs in blood, we must nurture a faith so profound that it bears the same witness, sacrificially dedicating our lives for Christ and the salvation of souls in whatever ways we are called.

SAINTS WENCESLAUS, MARTYR, AND LAWRENCE RUIZ AND COMPANIONS, MARTYRS, PRAY FOR US!