1Corinthians 2:12

February 16, 2022

Psalm 98: 1-3

February 17, 2022FEAST OF THE SEVEN HOLY FOUNDERS OF THE ORDER OF SERVITES

FEAST DAY – 17th FEBRUARY

RELIGIOUS (1198 – 17 February 1310)

The Order of Servites, or Servants of Mary, is an order of friars, who follow the rule of Saint Augustine. It was instituted in Italy in the thirteenth century by seven rich men of Florence, and has for its special object meditation on the Dolours of the most holy Virgin, that its members may feel and share them with her, and propagate this devotion among the faithful.

The coming of the Friars marks the very heart of the Middle Ages. St. Dominic was born in 1170, St. Francis in 1182, St. Bonfilius, the eldest of the Servites, in 1198; and the special task of each of the three Orders was closely allied to those of the others. St. Dominic took the doctrine of Christ as his charge, to preach it everywhere, and set it forth in all its splendour.

St. Francis embraced Christian morality, to practise its heroism, and show the inexpressible sweetness which underlay its most austere observances. The Seven Holy Founders of the Servite Order, like loving and tender children, devoted themselves to her, who had borne Christ Himself in her immaculate bosom, Christ, source of all truth and principle of all good; to her, the inseparable coadjutrix of Jesus in the redemption of souls; the Saviour sacrificed in His infinite love for the salvation and blessing of all men.

Thus while St. Dominic and St. Francis manifested Christ to those eager to know and to love Him, the seven Saints of Florence showed forth the sweet and radiant face of the Virgin, the Mother who from Bethlehem to Calvary encircles with the aureole of her love Him who wrought the glory of God, who is the Conqueror of souls.

Innocent III. was in the chair of St. Peter, brave among the distractions of the Christian world. Germany was a prey to civil war between the Emperor Otho IV. and Philip of Swabia; France was under the glorious rule of Philip Augustus who, having returned from the third Crusade, conquered Normandy, Maine, Anjou and Poitou, but showed himself a true son of the Church in submitting wholly to Innocent in the question of his marriage, having wished to repudiate his wife Ingeburge.

Not so John in England, more disloyal to the Holy See than any King of England, till he arose who brought about the great apostacy. Spain was in the agony of the Mahomedan invasion. In the East, Jerusalem had again fallen into the power of the Infidel, and the Pope incited and arranged the fourth Crusade. But the Eastern Empire alone fell, and the Holy Places were not freed.

Coming nearer to his own realm, the Pope looked out on a stormy and distracted land. Except the States of the Church and the kingdom of Sicily, then under a Regency, all the important towns were at strife with their neighbours, either forming round them independent communes, or becoming the centres of small republics, living in perpetual feud. Later, in Dante’s time, who probably knew some of the early Servite Saints, there were some seven entrenched camps belonging to different factions within the City of Florence itself.

The Church and the offices of religion constituted the whirlwind’s heart of peace, and the many confraternities to which pious laymen belonged, brought men together, who would not otherwise have known each other, of all opinions and all stations. In them, Guelf and Ghibelline, merchant and prince, met on an equal footing.

Such a Confraternity was that of the ” Laudesi,” or the Elder Society of Our Blessed Lady, founded in the year 1183. It was in fact just such a confraternity or sodality as we now know, mainly in connection with Jesuit churches, and under one of the titles of Our Lady. It was composed of the nobles and merchants of Florence, and met at the church of Santa Reparata. In the year 1233, just fifty years after its foundation, it numbered two hundred members, all of the best families in Florence, and was under the direction of a young priest, James of Poggibonsi.

Of these two hundred members, seven became the saintly founders of the Servite Order, and the Confraternity of the Laudesi was, in the good providence of God, to serve as their noviciate.

Bonfilius Monaldi was the eldest. He was born in 1198, the year of the election of Innocent III. The Monaldeschi, for such was the original name, were of French extraction, related to the royal House of Anjou. He was a young man of prayerful and ascetic life, who took the lead among his friends in all exercises of piety, so that, as soon as there was question among them of community life, they turned to him as their natural superior. He retained in religion his baptismal name.

Alexis Falconieri or Alexius Falcone, was born in 1200, of a noble family, originally of Fiesole, but long settled in Florence. He was the eldest son of Bernard Falconieri, a knight, and one of the merchant princes who created the greatness of his native city. He made his course at the University, studying what were then known as the Humanities, Latin and Greek, the usual classical course, as well as belles lettres, with great success; but he was marked as especially prayerful, fond of reading religious books, and avoiding general society. At an early age he vowed himself to celibacy long before he knew what outward form his life would take. He never became a priest, but remained Brother Alexis, keeping his own name.

Benedict de l’Antella was born in 1203, of a wealthy family, of foreign, perhaps German, or, as some think, Eastern extraction, who, long settled at Antella, had but recently come into Florence and become bankers. Benedict was extremely well educated, of remarkable beauty, and called on by his position to mix much in society. He was afterwards known in religion as Father Manettus.

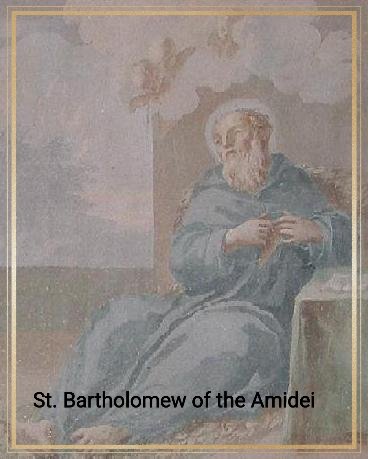

Bartholomew Amidei was born in 1204, of one of the oldest, richest, and most powerful families of the City. He claimed to be ancient Roman by origin. The Amidei were Ghibellines, and that Bartholomew received a most Christian education is among the many proofs that the bitter political strifes of the age were merely political, and hindered neither side from being good Catholics. His family, who lived much in the world, allowed him to follow a secluded and religious life, which found its natural development in a religious Order. He took in religion his family, rather than his baptismal, name.

Ricovero Uguccioni was born in the same year as Amidei, of a family both noble and mercantile. The lad was from a very early age remarkable for obedience, compassion for the poor, and love of solitude; devoted to pious reading, yet, a leader among his young companions who looked up to him. In religion, he was known as Hugh.

Gherardino Sostegni was born in 1205, of good family, but beyond this, little is known of his worldly state. In religion, he bore his family name Sostegni.

John Manetti was born in 1206; of the higher ranks of the Florentine aristocracy, both in birth and riches. In religion he was afterwards known as Fr. Buonagiunta, or Bienvenu.

Of these seven, the eldest was thirty-four, the youngest about twenty-seven, when their great change in life came to them. They lived in various quarters of the city, held divers views on politics, their one bond of union was the confraternity of Our Lady, though some among them knew one or two others with more or less intimacy. Monaldi, Amidei, Sostegni and Manetti were married, but Monaldi and perhaps another had already become widowers.

Alexis Falconieri alone had, as has been said, taken a vow, but Antella and Uguccioni showed plainly to their families that their wishes tended in the same direction. There were many reasons why even those who sought after perfection should in Italy, and at that time, enter into the marriage state. The Cathari, a sect of heretics who had great success in Florence, made light of marriage, and under pretence of purity were grossly immoral. It was as necessary to uphold true purity by affording examples of holy married life, as of celibacy. But these seven were especially eager to gain perfection, in which they were aided, and to which they were stimulated, by their director.

It had come to pass that Gregory IX in his pontificate gave special favour to two devotions, afterwards to be so closely associated with the servants of Mary. These were the Angelus and the Salve Regina. In 1230 Ardingo de Forasboschi became Bishop of Florence, himself a native of the city, and belonging to one of the great Guelf families. Both on religious and on social grounds he had an especial affection to the Laudesi.

On the Feast of the Assumption, August, 15th 1233, these seven young men, with other members of the Laudesi, having confessed and communicated, were each and all making their thanksgiving after Mass. Each, unknown to those about them, fell into an ecstasy. Each seemed to himself surrounded by supernatural light, in the midst of which Our Lady appeared to them accompanied by angels, who spoke to each of them the words; “Leave the world, retire together into solitude, that you may fight against yourselves, and live wholly for God. You will thus experience heavenly consolations. My protection and assistance will never fail you.”

The vision faded, the congregation dispersed, only the Seven remained, each meditating what the vision might mean. Bonfilius Monaldi, as the eldest, broke the silence, telling what had befallen him, saying he was ready to obey Our Lady’s call. Each recounted the same experiences, and resolve.

As Monaldi had been the first to speak, so it was decided that he must be the first to act; they looked to him for guidance. He decided to seek counsel of their director, James of Poggibonsi, who concluded that was no mere fancy of pious youths, but in fact, a call from their Mother, manifesting to them the will of God, to obey without hesitation.

Some were engaged in business, some in offices of state, four had family ties, which it was not easy to break, especially since the Church suffers no married man or woman to enter into religion unless the other party to the marriage contract does so too. It is believed that the two wives who still lived became afterwards Tertiaries of the Order; at any rate the conditions were at the time fulfilled, all social and worldly arrangements were made; and by the eighth of September, the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin, they were free to obey, they had stripped themselves of all that bound them to the world.

Meantime, and while waiting to know the further will of God, Monaldi and their director sketched out a plan of community life. They adopted a habit of grey wool, with a leathern cincture, and found a house just outside the city walls, where they might pass much of their time in solitude and prayer, yet near enough to the city to give an example to those they had so lately left. All this was done with the approval of the Bishop; it was merely a question of certain men living a mortified life in community; he granted permission to James to live with them as their chaplain, to celebrate Mass in their oratory, and to reserve the Blessed Sacrament.

So soon as their life arranged itself, and Monaldi was formally elected as their Superior, they desired to submit themselves to the Bishop for his blessing. He wished to see the whole Brotherhood. Their entry into Florence was a strange contrast to what they had seemed a few days before, a band of rich young men in all their splendor. Their appearance drew a crowd of sympathizers, who, recognizing their great renunciation and sanctity, pressed to touch their garments, to kiss their hands and entreat their blessing.

Suddenly, from the midst of the crowd, were heard the voices of children who cried: “Ecco, eceo i Servi di Maria:” “See, the Servants of Mary.” The same exclamation was made still more wonderfully on the following thirteenth of January, when, as two of the Brethren, Falconieri and Manetti, were asking charity in the city, again infants in arms gave them their title. One of these children was Philip Benizi, afterwards to be one of the greatest Saints of the Order and its General. He was then only five months old, and spoke for the first time in crying “Mother, those are Mary’s Servants, give them an alms.”

They had by this time, with the approbation of their Bishop, entered on a community life of mendicancy, devoting themselves especially to Our Lady, to whose honour they reserved Saturday in each week. The habitation without the city walls which had seemed to them at first so solitary, and so fitted for an eremitical life became soon thronged by troops of citizens, curious to see the recipients of so great favours; and they therefore began to say among themselves that they were not wholly obedient to the voice which had said as plainly as to the disciples of old “Come ye apart into a desert place, and rest awhile.”

There is a windy mountain ten miles to the north of Florence, a spur of the Apennines, lonely and savage; this again was manifested to each of them in a vision as the place of their future abode; while at the same time a voice, sweet and sonorous, distinct yet mysterious, told them that this mountain was called Monte Senario, that on its height they were to dwell, and apply themselves to yet greater austerity; that in this more rigorous and secluded life they might count always on the favour and succour of the Mother of God.

Monte Senario was part of the episcopal domain of Florence, and the Bishop willingly granted to the solitaries the territory whereon they desired to settle. At dawn of day, after receiving Holy Communion from their director, they skirted the walls of Florence in procession, carrying the Cross before them, and the image of the Blessed Virgin which had stood in their oratory. They climbed the mountain fasting, for it was the vigil of the Ascension; they grounded the Cross, and set down the statue of Our Lady to make their evening prayer, not knowing where they might put a shelter for the Blessed Sacrament after the Feast the next day.

They succeeded however in building a small shelter of boughs as a chapel, and so passed the last day of May, 1234. Their simple monastery, or rather hermitage, was built before the end of the same year; they dwelling till then in caves and crevices of the rocks. In this monastery they followed a mixture of hermit and community life, broken only by visits of two of their number each week to Florence in quest of alms, and by the acquisition of a small house of refuge in which they might shelter.

Their lives were one unceasing round of austerity and devotion, but their future was still uncertain; they had not ventured to form themselves into a religious Order, though encouraged to do so by their Bishop. They waited and prayed, and in their perplexity they asked a sign. It was given them somewhat as one was given to the Prophet Jonas when his gourd grew up in a night. Just below the crest of the mountain to the south, where there was some depth of richer soil, the hermits had planted a vine.

On the 3rd Sunday in Lent, February 27, 1239, the Brethren saw their vine clothed with green leaves and clusters of ripe grapes. All around smiled the verdure of spring, and the scent of flowers filled the air. They dared not interpret the prodigy. The superior despatched one of the community to tell to the Bishop the amazing news, and beg that he would give them counsel, for he was a man of most holy life, one to whom supernatural communication had already been vouchsafed.

To him in a dream heaven revealed the interpretation of the prodigy. The seven hermits were seven branches of the mystic vine, the clusters were those who should join themselves to the Order; the Brethren were again, though as Religious, to mingle in the world. As always they obeyed the divine voice given; Easter was near at hand, when they would open their ranks to those who came, till then they would give themselves to earnest prayer.

On Good Friday, April 13, 1240, which that year coincided with the Feast of the Annunciation, all for which the Seven Holy Founders had been preparing found its explanation. On the evening of that day, in their oratory, Our Lady once more appeared to them in a vision, surrounded by angels who bore in their hands religious habits of black, a book containing the Rule of St. Augustine, the title Servants of Mary written in letters of gold, and a palm branch.

Then holding in her own hands the habit with which she seemed to clothe each of them; she said: “I come, Servants well beloved and elect, I come to accomplish your desires and grant your prayers; here are the habits in which I wish you should in future be clothed; their black hue should always bring to mind the cruel Dolours which I felt by reason of the Crucifixion and Death of my only Son; the Rule of St. Augustine, which I give you as the form of your Religious Life, will gain for you the palm prepared in heaven, if you serve me faithfully on earth.” The vision vanished, and the foundation of the Servite Order was definitely accomplished.

But this was not all. Our Lady at the same hour appeared to the Bishop of Florence, and made to him the same communication. He gladly went to Monte Senario for their Clothing, and erected them so far as rested with him, into a formal Order, giving them their religious names, and allowing them to admit new members. Of these their Director, James of Poggibonsi, was the first. The Bishop also urged on the Seven to prepare for ordination, wherein all obeyed, Alexis Falconieri only excepted. Nothing could overcome the great humility in which he desired to remain Brother Alexis.

When the news of the vision went abroad, the affluence of new numbers was known. Other towns in North Italy desired to receive, and received, homes of the nascent Order, and of the new and special practices which distinguished them from others. Immediately–and to this day the practice remains.

They began their Mass with Ave Maria, and ended it with Salve Regina, adding other devotions also to Our Lady of Dolours, who under that title had given herself as their special patron. Blessed Bonfilius established also the Third Order, and the Society of the Black Scapular, both of these as well as the Devotions, seeming to appeal to the hearts and satisfying the needs of the time, and all things seemed to promise prosperity. But the Founders had to share in the dolours of their mother, and the time of peace was not yet.

Gregory IX. died in August, 1241, without having formally confirmed the Order, and his successor Celestine IV., who had for the Servites great esteem and affection, who had also visited them at Monte Senario, only lived a fortnight after his election. The See remained vacant for nearly two years, till Innocent IV. was elected in June, 1243. One of his earliest acts was to send Peter of Verona, a Dominican, afterwards known as St. Peter Martyr, as Inquisitor to Northern Italy, with a view to putting down the heresy of the Cathari, and incidentally to enquire into the life of the Religious of Monte Senario.

Peter of Verona conversed with Monaldi and Falconieri, and then prayed earnestly. He was answered by a vision in which Our Lady appeared to him, covered with a black mantle under which she sheltered Religious in the same habit, and in the company were those with whom he had spoken. Then he beheld angels gathering lilies, and among them were seven of surpassing whiteness, which Our Lady accepted, and placed in her bosom. The saint was convinced that the Order was of God, and after visiting Monte Senario reported favourably to the Pope.

This is no place to speak of the favours heaped on the Fathers by various Popes, nor the difficulties which cast shadows on their way, of their missionary efforts, nor the spread of the Order into other lands, even in the life time of the Founders. To do so would be to write the history of the Order, and far exceed our limit. We can but say a few words on their edifying lives, their holy deaths.

St. Bonfilius ruled the community till 1255, when after repeated endeavours, he succeeded in laying down his office, and the choice of the Fathers fell on St. Bonagiunta. Miracle had again marked him out as chosen of God. A merchant in the town, wearied by the Saint’s exhortations to virtue, under pretence of aiding the needs of the convent, offered bread and wine, into which he had introduced poison, for the special use of Fr. Bonagiunta. The Saint partook of the food, then, suspecting the evil, he made over it the sign of the cross; the wine flask burst into shards, the bread was in an instant full of worms; and the terrified servant who had, unwittingly, brought the gift, returned to find his master sick unto death.

St. Bonagiunta was the first to pass away. Worn with travel, always on foot, for the good of his Order, and the conversion of heretics, he felt his end approaching. On the last day of August 1257 he said Mass with extraordinary devotion, and, calling his brethren together, spoke in prophetic words, of trouble which was soon to fall on the Order; and then set himself to meditate aloud on the Passion.

When he came to the words “In manus tuas, Domine, commendo spiritum meum–Into Thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit,” he extended his arms in the form of a cross and fell forward against the altar. His brethren, among whom was St. Philip Benizi, at his wish, supported him in that position, and so kneeling at the tabernacle of his Lord, he breathed forth his soul.

St. Bonfilius was the next to hear his Master’s call. He was Vicar General in the absence of the third General in Germany and in France. He too retired to Monte Senario, and died on January 1st, 1262, “less of any definite disease than of those heavenly flames which burnt up his heart.” He and those around him were consoled by special revelations from her whose faithful servant he had been.

Three years later came the turn of St. Amideus. For a year he had remained at Monte Senario, constantly remaining whole hours alone in his grotto. Alone he died on the third Sunday after Easter, April 18th, 1265. His death was made known to his brethren by a wondrous sign. A tongue of fire shot from Monte Senario to heaven, while a sweet odour filled the whole convent: the Fathers did not doubt that, under this sign of flame, his heart, which had burnt with so vehement love, went to God.

He was succeeded by Fr. Manetti as General, and he in his turn by the young Philip Benizi, into whose hands when he had committed his charge, St. Manetti also retired to Monte Senario, and died in St. Philip’s arms. The three brave men who were left spared no fatigue. One, St. Alexis continued his hard life as a lay brother, two in spite of advancing years wore themselves with missionary labours in foreign lands with their new General, St. Philip.

In the spring of 1282, SS. Hugh and Sosthenes returned to Monte Senario. And as they went they spoke of all that their Lady had done for them, of the spread of the Order, of the deaths of those who had gone before. Raising their eyes to heaven, they desired to be united to their Sovereign God. Then they heard a voice which said: “Fear hot, ye men of God, your consolation is at hand.” At once on their arrival they were stricken with fever, and died at the same hour on May 3rd, 1282.

St. Philip Benizi was at that time in Florence, and, praying, he fell into a trance. He saw on Monte Senario, two angels pluck each a lily of perfect whiteness, and present them to Our Lady. He called his brethren around him, and knowing well what the vision meant, announced to them the deaths of the two holy Founders.

Not till 1310 was St. Alexis called away. In his last years it was only in virtue of holy obedience that he allowed himself to lie on a couch of straw, and to relax his rule of rigid abstinence. When he knew that his hour was come he called his brethren round him, and recited one hundred Aves, during which the angels circled around him in the form of doves. As he recited the last Ave he saw our Lord approach, and crown him with sweet flowers. He cried: “Kneel my Brothers, see ye not Jesus Christ, your loving Lord and mine, who crowns me with a garland of beauteous flowers? Worship Him and adore. He will crown you also in the same manner, if, full of devotion to the holy Virgin, you imitate her immaculate purity, her profound humility.”

So closed the life story of the Seven Founders, who, during the time they spent on earth, did all that in them lay to hide their merits under the veil of profound humility. Their sanctity was attested, not only by their heroic virtues, as they came to light, and by the miracles which accompanied them in their career, and illuminated their deaths, but also by an whole generation of saints, who arose on their traces, and became, as it were, their guard of honour.

Foremost of these was St. Philip Benizi, whom we have so often named, whose life merits a separate essay. He was the most brilliant disciple of the Seven Founders, and did honour to his masters by his work and sanctity. Indeed so great was the renown of his virtue, that he seemed even to cast into the shade the heroism of those who formed his character, as he is their abiding honour. No other ever reflected their spirit more faithfully, seized their thought more accurately, carried out their designs with such fidelity. Philip made a saint by saints, was in his turn the father of saints, of whom SS. Peregrine Laziosi and Juliana Falconieri, foundress of the Mantellate or Servite nuns, are the best known.

The spread of the Order in its early days was remarkable, and it was soon divided into six provinces, containing about one hundred convents, four provinces in Italy, one consisting of Germany, one of France. Only in these later days has the order spread to England and to America, where to it, as to the Catholic Church in general, a vast field seems opening.

In the course of the year 1752, after more than four hundred years, the Seven Holy Fathers were solemnly declared Blessed, and in 1888 they were canonized. Lovely and pleasant in their lives, in death they were not divided; the miracles necessary to their canonization were not wrought separately amongst them; all together continue the work they began in common.

PATRON: Invoked to aid in the imitation of the charity and patience of Our Lady of Sorrows.

PRAYER:

Impart to us, O Lord, in kindness, the filial devotion with which the holy brothers venerated so devoutly the Mother of God and led your people to yourself.

Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God for ever and ever. Amen