Proverbs 4: 23

June 21, 2022

Proverbs 9:10

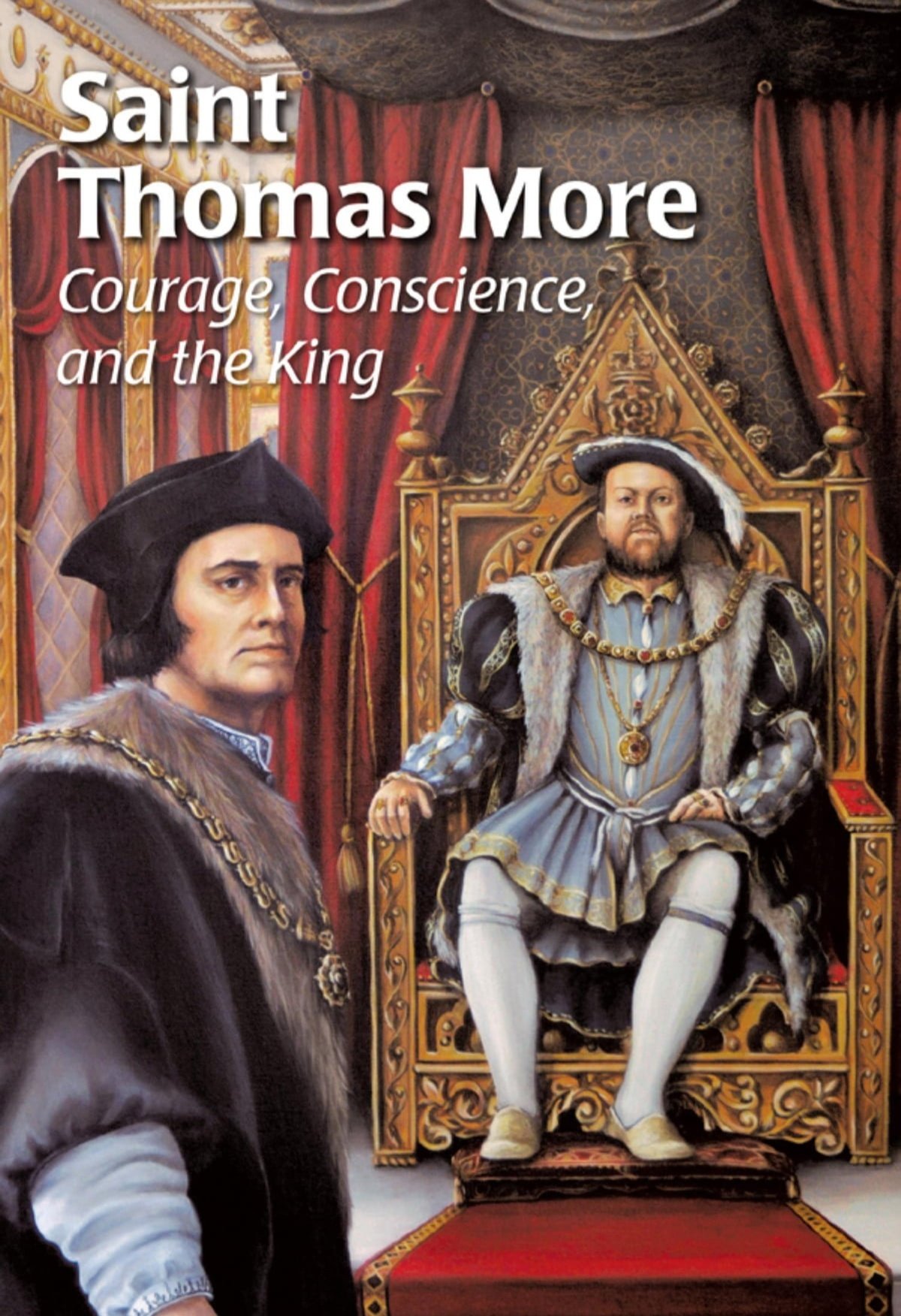

June 22, 2022FEAST OF SAINT THOMAS MORE, BISHOP AND MARTYR

FEAST DAY – 22nd JUNE

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lord High Chancellor of England from October 1529 to May 1532. He wrote Utopia, published in 1516, which describes the political system of an imaginary island state.

More opposed the Protestant Reformation, directing polemics against the theology of Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin and William Tyndale. More also opposed Henry VIII’s separation from the Catholic Church, refusing to acknowledge Henry as supreme head of the Church of England and the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon.

After refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy, he was convicted of treason and executed. On his execution, he was reported to have said: “I die the King’s good servant, and God’s first”. Pope Pius XI canonised More in 1935 as a martyr. Pope John Paul II in 2000 declared him the patron saint of statesmen and politicians.

Born on Milk Street in the City of London, on 7 February 1478, Thomas More was the son of Sir John More, a successful lawyer and later a judge, and his wife Agnes (née Graunger). He was the second of six children. More was educated at St. Anthony’s School , then considered one of London’s best schools. From 1490 to 1492, More served John Morton, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor of England, as a household page.

Morton enthusiastically supported the “New Learning” (scholarship which was later known as “humanism” or “London humanism”), and thought highly of the young More. Believing that More had great potential, Morton nominated him for a place at the University of Oxford (either in St. Mary Hall or Canterbury College, both now gone).

More began his studies at Oxford in 1492, and received a classical education. Studying under Thomas Linacre and William Grocyn, he became proficient in both Latin and Greek. More left Oxford after only two years—at his father’s insistence—to begin legal training in London at New Inn, one of the Inns of Chancery. In 1496, More became a student at Lincoln’s Inn, one of the Inns of Court, where he remained until 1502, when he was called to the Bar.

According to his friend, the theologian Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam, More once seriously contemplated abandoning his legal career to become a monk. Between 1503 and 1504 More lived near the Carthusian monastery outside the walls of London and joined in the monks’ spiritual exercises. Although he deeply admired their piety, More ultimately decided to remain a layman.

He stood for election to Parliament in 1504 and married the following year. More continued ascetic practices for the rest of his life, such as wearing a hair shirt next to his skin and occasionally engaging in self-flagellation. A tradition of the Third Order of Saint Francis, honours More as a member of that Order on their calendar of saints.

More married Jane Colt in 1505. In that year he leased a portion of a house known as the Old Barge (originally there had been a wharf nearby serving the Walbrook river) on Bucklersbury, St Stephen Walbrook parish, London. Eight years later he took over the rest of the house and in total he lived there for almost 20 years, until his move to Chelsea in 1525.

Erasmus reported that More wanted to give his young wife a better education than she had previously received at home, and tutored her in music and literature. The couple had four children: Margaret, Elizabeth, Cicely, and John. Jane died in 1511. Going “against friends’ advice and common custom,” within 30 days, More had married one of the many eligible women among his wide circle of friends.

He chose Alice Middleton, a widow, to head his household and care for his small children. The speed of the marriage was so unusual that More had to get a dispensation from the banns of marriage, which, due to his good public reputation, he easily obtained. More had no children from his second marriage, although he raised Alice’s daughter from her previous marriage as his own.

More also became the guardian of two young girls: Anne Cresacre would eventually marry his son, John More and Margaret Giggs (later Clement) who was the only member of his family to witness his execution (she died on the 35th anniversary of that execution, and her daughter married More’s nephew William Rastell). An affectionate father, More wrote letters to his children whenever he was away on legal or government business, and encouraged them to write to him often.

More insisted upon giving his daughters the same classical education as his son, an unusual attitude at the time. His eldest daughter, Margaret, attracted much admiration for her erudition, especially her fluency in Greek and Latin. More told his daughter of his pride in her academic accomplishments in September 1522, after he showed the bishop a letter she had written.

More’s decision to educate his daughters set an example for other noble families. Even Erasmus became much more favourable once he witnessed their accomplishments. In 1504, More was elected to Parliament to represent Great Yarmouth, and in 1510 began representing London.

From 1510, More served as one of the two undersheriffs of the City of London, a position of considerable responsibility in which he earned a reputation as an honest and effective public servant. More became Master of Requests in 1514, the same year in which he was appointed as a Privy Counsellor. More undertook a diplomatic mission to the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, accompanying Thomas Wolsey, Cardinal Archbishop of York, to Calais and Bruges.

More was later knighted and made under-treasurer of the Exchequer in 1521. As secretary and personal adviser to King Henry VIII, More became increasingly influential, welcoming foreign diplomats, drafting official documents, and serving as a liaison between the King and Lord Chancellor Wolsey. He later served as High Steward for the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

In 1523 More was elected as knight of the shire (MP) for Middlesex and, on Wolsey’s recommendation, the House of Commons elected More its Speaker. In 1525 More became Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster, with executive and judicial responsibilities over much of northern England.

In 1533, More refused to attend the coronation of Anne Boleyn as the Queen of England. Technically, this was not an act of treason, as More had written to Henry seemingly acknowledging Anne’s queenship and expressing his desire for the King’s happiness and the new Queen’s health. His refusal to attend was widely interpreted as a snub against Anne, and Henry took action against him.

Shortly thereafter, More was charged with accepting bribes, but the charges had to be dismissed for lack of any evidence. In early 1534, More was accused by Thomas Cromwell of having given advice and counsel to the “Holy Maid of Kent,” Elizabeth Barton, a nun who had prophesied that the king had ruined his soul and would come to a quick end for having divorced Queen Catherine.

This was a month after Barton had confessed, which was possibly done under royal pressure, and was said to be concealment of treason. Though it was dangerous for anyone to have anything to do with Barton, More had indeed met her, and was impressed by her fervour. But More was prudent and told her not to interfere with state matters.

More was called before a committee of the Privy Council to answer these charges of treason, and after his respectful answers the matter seemed to have been dropped. On 13 April 1534, More was asked to appear before a commission and swear his allegiance to the parliamentary Act of Succession.

More accepted Parliament’s right to declare Anne Boleyn the legitimate Queen of England, though he refused “the spiritual validity of the king’s second marriage”, and, holding fast to the teaching of papal supremacy, he steadfastly refused to take the oath of supremacy of the Crown in the relationship between the kingdom and the church in England.

More furthermore publicly refused to uphold Henry’s annulment from Catherine. John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, refused the oath along with More. The oath reads:

…By reason whereof the Bishop of Rome and See Apostolic, contrary to the great and inviolable grants of jurisdictions given by God immediately to emperors, kings and princes in succession to their heirs, hath presumed in times past to invest who should please them to inherit in other men’s kingdoms and dominions, which thing we your most humble subjects, both spiritual and temporal, do most abhor and detest…

In addition to refusing to support the King’s annulment or supremacy, More refused to sign the 1534 Oath of Succession confirming Anne’s role as queen and the rights of their children to succession. More’s fate was sealed. While he had no argument with the basic concept of succession as stated in the Act, the preamble of the Oath repudiated the authority of the Pope.

His enemies had enough evidence to have the King arrest him on treason. Four days later, Henry had More imprisoned in the Tower of London. There More prepared a devotional Dialogue of Comfort against Tribulation. While More was imprisoned in the Tower, Thomas Cromwell made several visits, urging More to take the oath, which he continued to refuse.

The charges of high treason related to More’s violating the statutes as to the King’s supremacy (malicious silence) and conspiring with Bishop John Fisher in this respect (malicious conspiracy) and, according to some sources, included asserting that Parliament did not have the right to proclaim the King’s Supremacy over the English Church.

One group of scholars believes that the judges dismissed the first two charges (malicious acts) and tried More only on the final one, but others strongly disagree. Regardless of the specific charges, the indictment related to violation of the Treasons Act 1534 which declared it treason to speak against the King’s Supremacy.

“If any person or persons, after the first day of February next coming, do maliciously wish, will or desire, by words or writing, or by craft imagine, invent, practise, or attempt any bodily harm to be done or committed to the king’s most royal person, the queen’s, or their heirs apparent, or to deprive them or any of them of their dignity, title, or name of their royal estates … That then every such person and persons so offending … shall have and suffer such pains of death and other penalties, as is limited and accustomed in cases of high treason.”

The trial was held on 1 July 1535, before a panel of judges that included the new Lord Chancellor, Sir Thomas Audley, as well as Anne Boleyn’s uncle, Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, her father Thomas Boleyn and her brother George Boleyn. Norfolk offered More the chance of the king’s “gracious pardon” should he “reform his obstinate opinion”. More responded that, although he had not taken the oath, he had never spoken out against it either and that his silence could be accepted as his “ratification and confirmation” of the new statutes.

Thus More was relying upon legal precedent and the maxim “qui tacet consentire videtur” (“one who keeps silent seems to consent”), understanding that he could not be convicted as long as he did not explicitly deny that the King was Supreme Head of the Church, and he therefore refused to answer all questions regarding his opinions on the subject.

Thomas Cromwell, at the time the most powerful of the King’s advisors, brought forth Solicitor General Richard Rich to testify that More had, in his presence, denied that the King was the legitimate head of the Church. This testimony was characterised by More as being extremely dubious. Witnesses Richard Southwell and Mr. Palmer (a servant to Southwell) were also present and both denied having heard the details of the reported conversation. As More himself pointed out:

Can it therefore seem likely to your Lordships, that I should in so weighty an Affair as this, act so unadvisedly, as to trust Mr. Rich, a Man I had always so mean an Opinion of, in reference to his Truth and Honesty, … that I should only impart to Mr. Rich the Secrets of my Conscience in respect to the King’s Supremacy, the particular Secrets, and only Point about which I have been so long pressed to explain my self? which I never did, nor never would reveal; when the Act was once made, either to the King himself, or any of his Privy Councillors, as is well known to your Honours, who have been sent upon no other account at several times by his Majesty to me in the Tower. I refer it to your Judgments, my Lords, whether this can seem credible to any of your Lordships.

The jury took only fifteen minutes, however, to find More guilty. After the jury’s verdict was delivered and before his sentencing, More spoke freely of his belief that “no temporal man may be the head of the spirituality” (take over the role of the Pope). According to William Roper’s account, More was pleading that the Statute of Supremacy was contrary to the Magna Carta, to Church laws and to the laws of England, attempting to void the entire indictment against him.

He was sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered (the usual punishment for traitors who were not the nobility), but the King commuted this to execution by decapitation. The execution took place on 6 July 1535 at Tower Hill. When he came to mount the steps to the scaffold, its frame seeming so weak that it might collapse, More is widely quoted as saying (to one of the officials): “I pray you, master Lieutenant, see me safe up and [for] my coming down, let me shift for my self”; while on the scaffold he declared that he died “the king’s good servant, and God’s first.”

After More had finished reciting the Miserere while kneeling, the executioner reportedly begged his pardon, then More rose up merrily, kissed him and gave him forgiveness. Another comment he is believed to have made to the executioner is that his beard was completely innocent of any crime, and did not deserve the axe; he then positioned his beard so that it would not be harmed.

More asked that his foster/adopted daughter Margaret Clement (née Giggs) be given his headless corpse to bury. She was the only member of his family to witness his execution. He was buried at the Tower of London, in the chapel of St Peter ad Vincula in an unmarked grave. His head was fixed upon a pike over London Bridge for a month, according to the normal custom for traitors.

More’s daughter Margaret later rescued the severed head. It is believed to rest in the Roper Vault of St Dunstan’s Church, Canterbury, perhaps with the remains of Margaret and her husband’s family. Some have claimed that the head is buried within the tomb erected for More in Chelsea Old Church. Among other surviving relics is his hair shirt, presented for safe keeping by Margaret Clement.

This was long in the custody of the community of Augustinian canonesses who until 1983 lived at the convent at Abbotskerswell Priory, Devon. Some sources, including one from 2004, claimed that the shirt, made of goat hair was then at the Martyr’s church on the Weld family’s estate in Chideock, Dorset. It is now preserved at Buckfast Abbey, near Buckfastleigh in Devon.

Pope Leo XIII beatified Thomas More, John Fisher, and 52 other English Martyrs on 29 December 1886. Pope Pius XI canonised More and Fisher on 19 May 1935, and More’s feast day was established as 9 July. Since 1970 the General Roman Calendar has celebrated More with St John Fisher on 22 June (the date of Fisher’s execution). On 31 October 2000 Pope John Paul II declared More “the heavenly Patron of Statesmen and Politicians”.

More is the patron of the German Catholic youth organisation Katholische Junge Gemeinde. In 1980, despite their opposition to the English Reformation, More and Fisher were added as martyrs of the reformation to the Church of England’s calendar of “Saints and Heroes of the Christian Church”, to be commemorated every 6 July the date of More’s execution.

PRAYER

Lord God, we thank You for giving us St. Thomas More as an example of holiness in everyday lay life. Help us to follow his holy example. May we model his virtue and piety as we live out our own vocations.

St. Thomas, your love of God was so strong that you desired to live a life devoted to Him. You found a way devote your life to Him even while you lived in the world as a lawyer. Even though you lived among worldly people, you did not become worldly. You remained holy in your everyday life and prepared yourself for your ultimate test of faith.

Pray for me, that I may practice virtue in my daily life as you did, so that I may be ready when my faith is tested. We ask this through Christ Our Lord. Amen

(Source: praymorenovenas.com)